What is React?

Whether you're brand new to building dynamic web applications or you've been working with React for a long time, let's contextualize the most widely used UI framework in the world: React.

One thing that I like about React is that it allows me to write my components like little black boxes of abstraction. I can look at a design and draw lines around the UI elements and I know the components that I'm going to be making:

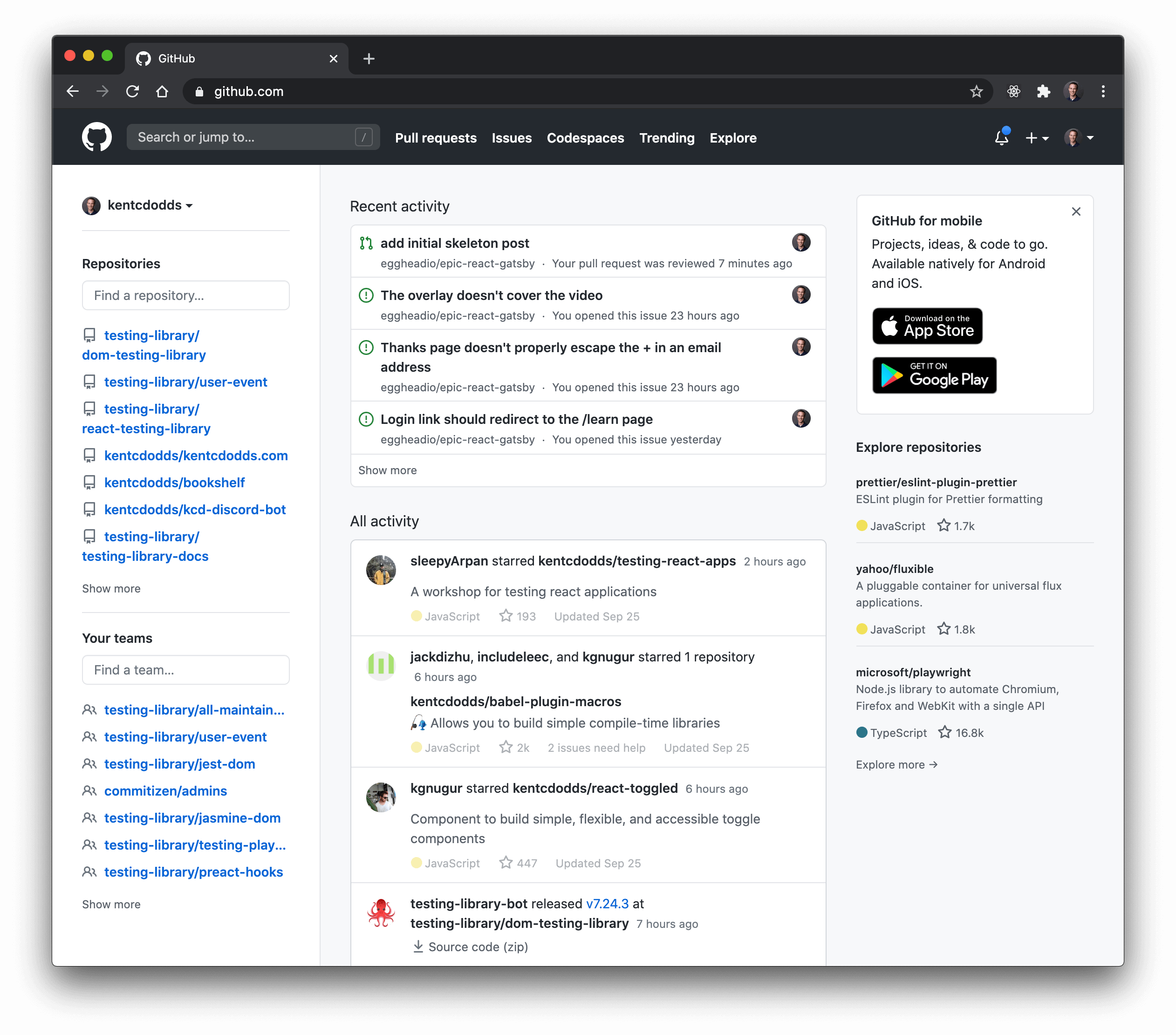

For example, here's my GitHub home page:

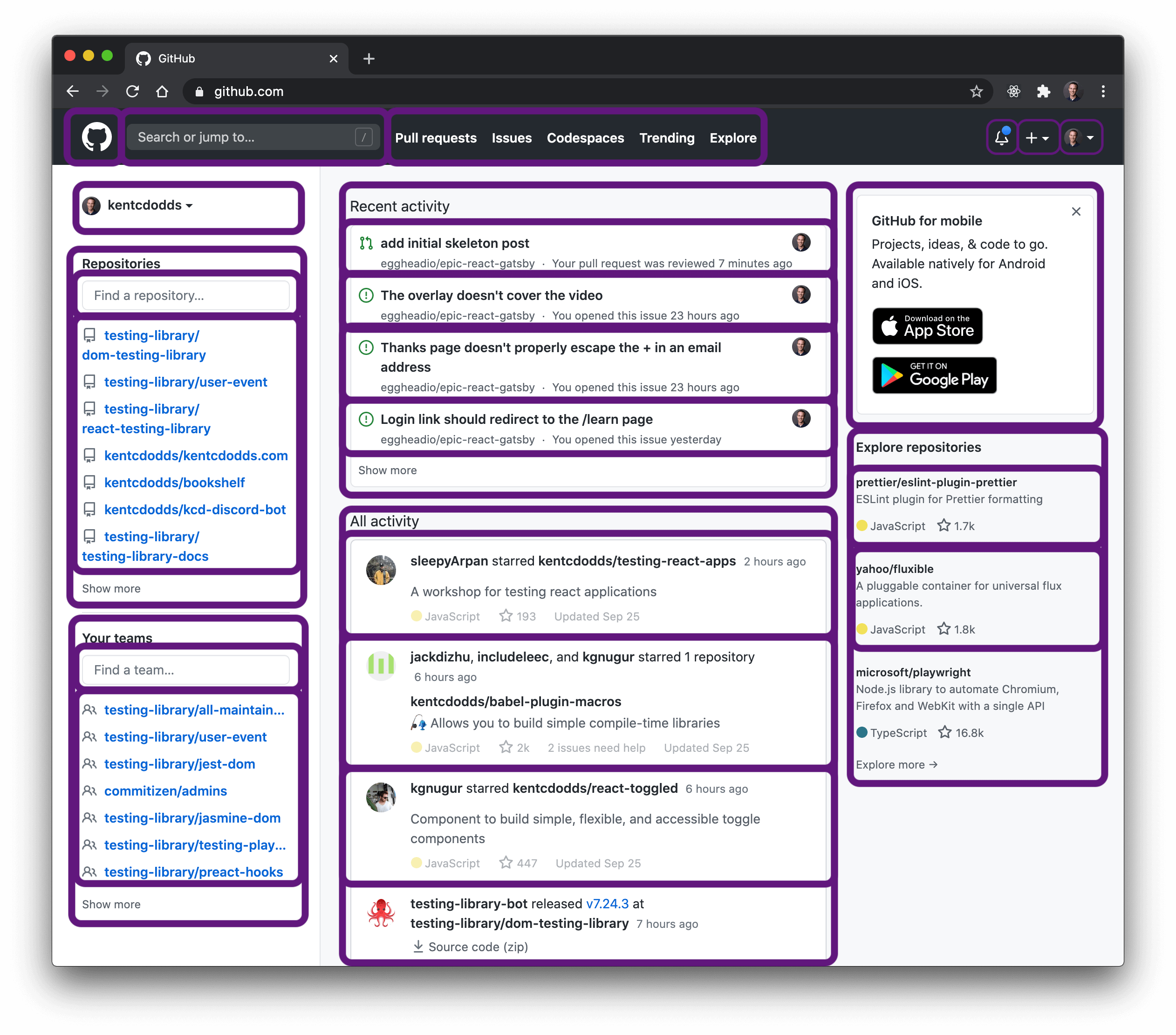

Can you identify the different components you might create out of this design? Here's how I look at it:

Now, you might not need an individual component for all of these things, or you may want more components. It really depends on a variety of factors we won't get into here. The mistake I want to point out is that the way we compose these UI elements together in our code often makes a drastic difference on how maintainable it is (as well as how often we feel "prop-drilling" pains).

Let's imagine how we might structure some of the components for this page:

function App() { return ( <div> <MainNav /> <Homepage /> </div> )}function MainNav() { return ( <div> <GitHubLogo /> <SiteSearch /> <NavLinks /> <NotificationBell /> <CreateDropdown /> <ProfileDropdown /> </div> )}function Homepage() { return ( <div> <LeftNav /> <CenterContent /> <RightContent /> </div> )}function LeftNav() { return ( <div> <DashboardDropdown /> <Repositories /> <Teams /> </div> )}function CenterContent() { return ( <div> <RecentActivity /> <AllActivity /> </div> )}function RightContent() { return ( <div> <Notices /> <ExploreRepos /> </div> )}

We could keep going, but I think that's sufficient. You may have structured this differently (or come up with a better name than RightContent 🤦♂️), but based on apps that I've built in the past as well as apps I've seen others build, this is a pretty typical structure. Before I talk about some potential issues, let me show you an alternative structure that takes advantage of React's brilliant composition model. Then we can talk about the improvements and trade-offs.

function App() { return ( <div> <MainNav> <GitHubLogo /> <SiteSearch /> <NavLinks /> <NotificationBell /> <CreateDropdown /> <ProfileDropdown /> </MainNav> <Homepage leftNav={ <LeftNav> <DashboardDropdown /> <Repositories /> <Teams /> </LeftNav> } centerContent={ <CenterContent> <RecentActivity /> <AllActivity /> </CenterContent> } rightContent={ <RightContent> <Notices /> <ExploreRepos /> </RightContent> } /> </div> )}function MainNav({children}) { return <div>{children}</div>}function Homepage({leftNav, centerContent, rightContent}) { return ( <div> {leftNav} {centerContent} {rightContent} </div> )}function LeftNav({children}) { return <div>{children}</div>}function CenterContent({children}) { return <div>{children}</div>}function RightContent({children}) { return <div>{children}</div>}

What's your initial reaction to this? Shock? Awe? Curiosity? Confusion? Disgust? Is your initial reaction based on the fact that this is unfamiliar to you and therefore should be shunned? If that's the case, then I invite you to pause and consider this for a moment.

First, let me be clear that this use of React's composition capabilities can probably be taken too far. Everything with moderation. The idea here is that our structural components are responsible for layout. They likely won't do much to manage state themselves (though they certainly could). They simply accept the different stateful elements and then lay them out onto the page in the places where they're supposed to appear. Most of the time, the children prop is sufficient (in the Angular.js world, we call this "transclusion"), but sometimes you might have several elements that you need to lay out, so you can use specific and named props like our Homepage component (in the Vue.js world, we call this "slots").

So, why would we do this? The biggest and best reason to do this is for state management. We're not showing any state use here, but let's imagine for a moment that we needed to pass the user around. Consider the first example. Where would you store the user's information? You'd probably store it in the App component because that's the "lowest common parent" of the components that require that state. From there you'd have to pass the user's information (and potentially mechanisms to update the user's information) as props.

This results in "prop-drilling". For example: <App /> -> <Homepage /> -> <CenterContent /> -> <AllActivity /> (and potentially further). People have a pretty low tolerance for this, so you're probably think that you'd use React's context API to solve this instead (so would I).

But consider what this would look like for our second, more composed example. You'd still need to store the user state in the App component, but what does it look like to get the user's info to the AllActivity component now? <App /> -> <AllActivity />. Boom. That's it.

I think too many people go from "passing props" -> "context" too quickly. If we structure our components with more composition in mind, then I think our codebase will be more maintainable (you'll likely not need to open so many files when you make changes) and we'll have fewer performance and state management problems.

I'm excited to show you more on EpicReact.Dev!

Delivered straight to your inbox.

Whether you're brand new to building dynamic web applications or you've been working with React for a long time, let's contextualize the most widely used UI framework in the world: React.

Understanding server-side waterfalls with RSCs and client-side waterfalls we're familiar with and why server-side waterfalls are probably better.

Forms can get slow pretty fast. Let's explore how state colocation can keep our React forms fast.

How and why I import react using a namespace